We begin our Lenten book study of Max Vincent’s book, Because of This I Rejoice, with the introduction: Laughing on Ash Wednesday. For those long familiar with Ash Wednesday, I imagine your first reaction to Vincent’s introduction title is something like, “wait, does he even know what Ash Wednesday is about?” Vincent says as much himself as he describes friends’ surprise at his joyfulness and enthusiasm for a day filled with dusty ashes, penitential prayers, kneeling, and a very particular focus on human mortality. It would seem the most hopeful thing one could think about Ash Wednesday would be a pleasant relief it lasts for 24 hours rather than a season. But this isn’t Vincent’s understanding, and a reflective read of the introduction helps us to prayerfully discover his joy.

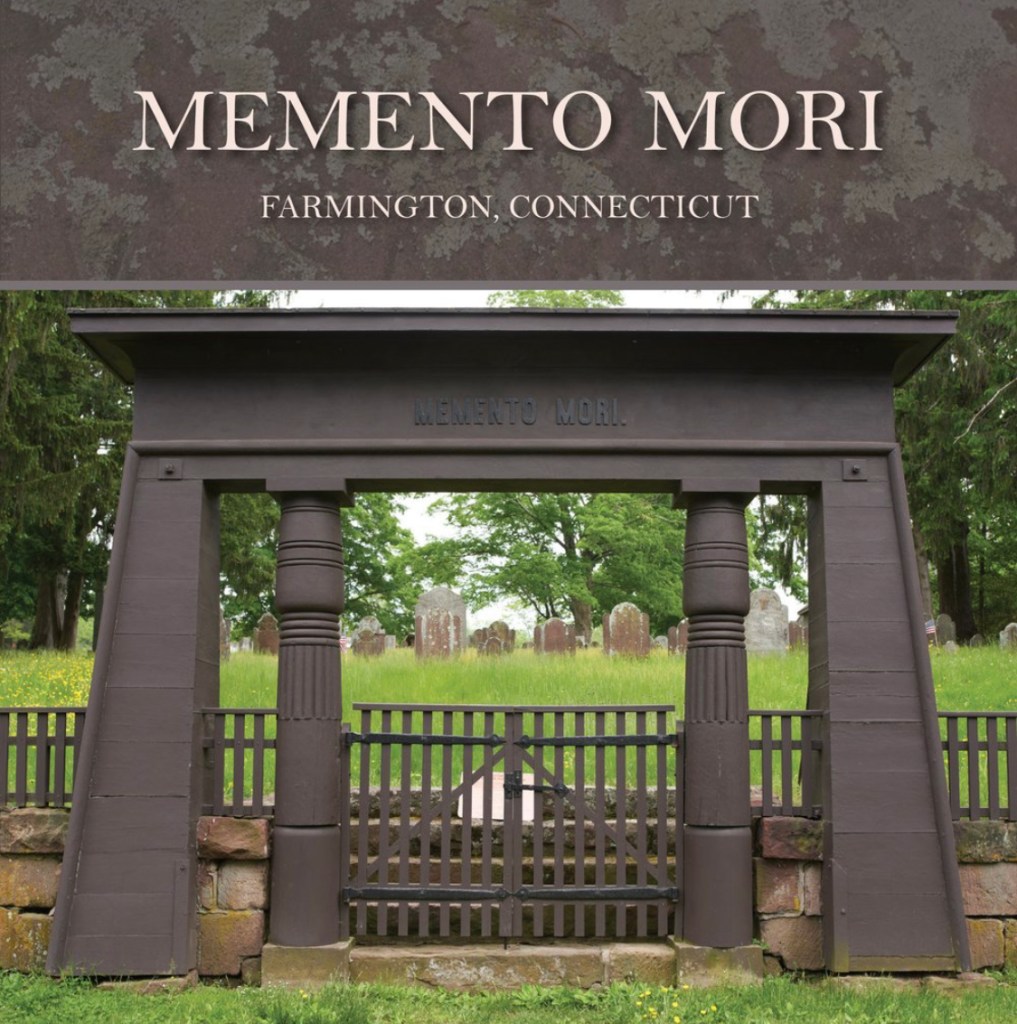

I have spent countless hours performing family research (genealogy is a hobby of mine) and many of my ancestors spent their lives in Farmington, CT, since the early 1600’s; and many of these folks are buried in the cemetery located in the center of the old village. The cemetery is known by the inscription above the gate to the grounds: Memento Mori, which means “remember death” or “remember your mortality.” Built in an age when it was never taken for granted a newborn would reach adulthood, these seemingly ominous words were really meant to be a reminder of the miracle of life, and an “advertisement” to be aware of the blessings of every day, for who really was sure of any blessing beyond those already given and received. I honestly believe these words were meant to give perspective on the present joys of life and to connect the living to those who had gone before them, remembering the good examples of their life and joy in God as well. Ash Wednesday, understood in this way, opens for us the possibilities of the joy and laughter that Vincent invites us to consider.

After a few opening paragraphs, Vincent begins to explain the joyful perspective of Lent in the section, “Denying Self, Acknowledging God.” He describes the spiritual approach of the Apostle Paul, writer of the Letter to the Philippians (which is the main source of Scripture the book follows), and explains how a life shaped after the cross and the Gospel of Christ is able to find joy in Lent. Vincent writes, “Time given up for spiritual practices should be joyful experiences of God’s grace working in and through us. Fasting is not about proving our love to God but about ridding ourselves of loves that compete with or stifle our awareness of God’s love and claim for us.” I believe this “ridding ourselves of loves that compete or stifle” our awareness of God is exactly the lesson of “Memento Mori” taught all those years ago. I also believe this thinking was the engine that drove the Apostle Paul all around the Mediterranean and beyond: he was filled with the joy of the Good News and couldn’t stop until he told everyone the life saving news! (Vincent explores this in more detail with his chapter end reflection questions). If we live “cross centered”, “Gospel centered” lives, as Vincent describes, where does this lead us? He writes, “Focusing less on ourselves and more on how these practices connect us to Christ imbues the activities with joy…Something at the heart of Christian living makes these disciplines not drudgery but rather joyful expressions of the life of faith. That “something” is the Gospel.”

Lent invites us to prayerfully reflect on our human frailty and the mortality of life – our memento mori. We are invited to consider our lives with God, in Christ, not as a tenuous, broken affair, but as a beautiful, unfolding covenant. When human life unfolds, sometimes things don’t go as planned and the edges of life collide, but with humility, persistence, and the love of God – life gets back on track, God’s grace is always enough, and the promise of new life points us toward our Risen Christ.